Dynamic Shear Rheometer

一、 Overview

The dynamic shear rheometer (DSR) (Figure 1 and Figure 185) is used to characterize the viscous and elastic behavior of asphalt binders at medium to high temperatures. This characterization is used in the Superpave PG asphalt binder specification. As with other Superpave binder tests, the actual temperatures anticipated in the area where the asphalt binder will be placed determine the test temperatures used.

Figure 185: Dynamic shear rheometer.

Figure 185: Dynamic shear rheometer.

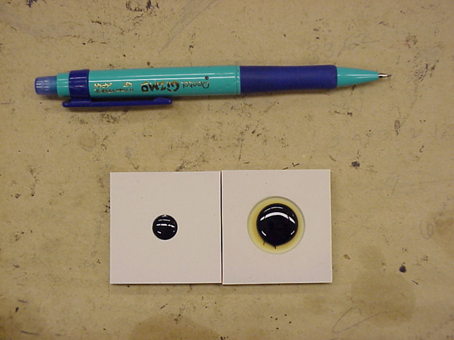

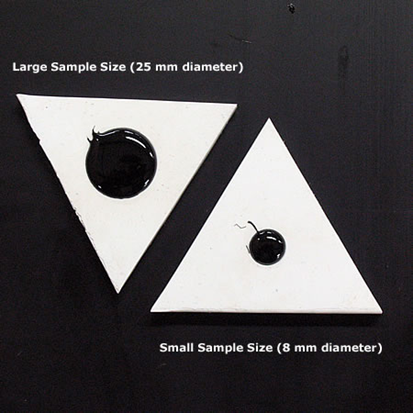

The basic DSR test uses a thin asphalt binder sample (Figure 186) sandwiched between two circular

plates. The lower plate is fixed while the upper plate oscillates back and forth across the sample

at 10 rad/sec (1.59 Hz) to create a shearing action (

Figure 186: DSR Samples

Figure 186: DSR Samples

The standard dynamic shear rheometer test is:

- AASHTO T 315: Determining the Rheological Properties of Asphalt Binder Using a Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR)

Background

Asphalt binders are viscoelastic. This means they behave partly like an elastic solid (deformation due to loading is recoverable – it is able to return to its original shape after a load is removed) and partly like a viscous liquid (deformation due to loading is non-recoverable – it cannot return to its original shape after a load is removed). Having been used in the plastics industry for years, the DSR is capable of quantifying both elastic and viscous properties. This makes it well suited for characterizing asphalt binders in the in-service pavement temperature range.

The DSR measures a specimen’s complex shear modulus (G*) and phase angle (δ). The complex shear modulus (G*) can be considered the sample’s total resistance to deformation when repeatedly sheared, while the phase angle (δ), is the lag between the applied shear stress and the resulting shear strain (Figure 5). The larger the phase angle (δ), the more viscous the material. Phase angle (δ) limiting values are:

- Purely elastic material: δ = 0 degrees

- Purely viscous material: δ = 90 degrees

The specified DSR oscillation rate of 10 radians/second (1.59 Hz) is meant to simulate the shearing action corresponding to a traffic speed of about 55 mph (90 km/hr).

DSR Superpave Specification Logic

G* and δ are used as predictors of HMA rutting and fatigue cracking. Early in pavement life rutting is the main concern, while later in pavement life fatigue cracking becomes the major concern.

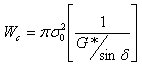

Rutting Prevention

In order to resist rutting, an asphalt binder should be stiff (it should not deform too much) and it should be elastic (it should be able to return to its original shape after load deformation). Therefore, the complex shear modulus elastic portion, G*/sinδ (Figure 6), should be large. When rutting is of greatest concern (during an HMA pavement’s early and mid-life), a minimum value for the elastic component of the complex shear modulus is specified. Intuitively, the higher the G* value, the stiffer the asphalt binder is (able to resist deformation), and the lower the δ value, the greater the elastic portion of G* is (able to recover its original shape after being deformed by a load).

Another way to look at this is that rutting is basically a cyclic loading phenomenon. With each traffic cycle, work is being done to deform the pavement surface. Part of this work is recovered by the elastic rebound of the pavement surface, while part is dissipated in the form of permanent deformation, heat, cracking and crack propagation. Therefore, in order to minimize rutting, the amount of work dissipated per loading cycle should be minimized. The work dissipated per loading cycle at a constant stress can be expressed as:

Where:

Figure 186: DSR Samples

Figure 186: DSR Samples

- Wc = work dissipated per load cycle

- σ = stress applied during load cycle

- G* = complex modulus

- δ = phase angle

In order to minimize the work dissipated per loading cycle, the parameter G*/sinδ should be be maximized. Therefore, minimum values for G*/sinδ for the DSR tests conducted on unaged asphalt binder and RTFO aged asphalt binder are specified.

Fatigue Cracking Prevention

In order to resist fatigue cracking, an asphalt binder should be elastic (able to dissipate energy by rebounding and not cracking) but not too stiff (excessively stiff substances will crack rather than deform-then-rebound). Therefore, the complex shear modulus viscous portion, G*sinδ (Figure 5), should be a minimum. When fatigue cracking is of greatest concern (late in an HMA pavement’s life), a maximum value for the viscous component of the complex shear modulus is specified.

Another way to look at this is that fatigue cracking can be considered a stress-controlled phenomenon in thick HMA pavements and a strain-controlled phenomenon in thin HMA pavements. Since fatigue cracking is more prevalent in thin pavements, the parameter of most concern for fatigue resistance can be considered a strain-controlled one. With each traffic cycle, work is being done to deform the pavement surface. Part of this work is recovered by the elastic rebound of the pavement surface, while part is dissipated in the form of permanent deformation, heat, cracking and crack propagation. The lower the amount of energy dissipated per loading cycle the less likely fatigue cracking is. Therefore, in order to minimize fatigue cracking the amount of work dissipated per loading cycle should be minimized. The work dissipated per loading cycle at a constant strain can be expressed as:

Where:

- Wc = work dissipated per load cycle

- ε0 = strain during load cycle

- G* = complex modulus

- δ = phase angle

This relationship between G*sinδ and fatigue cracking is more tenuous than the rutting relationship.

In order to minimize the work dissipated per loading cycle, the parameter G*sinδ should be minimized. Therefore, maximum values for G*sinδ for the DSR tests conducted on PAV aged asphalt binder are specified.

二、 Test Description

The following description is a brief summary of the test. It is not a complete procedure and should not be used to perform the test. The complete test procedure can be found in:

- AASHTO T 315: Determining the Rheological Properties of Asphalt Binder Using a Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR)

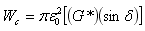

Summary

A small sample of asphalt binder is sandwiched between two plates. The test temperature, specimen size and plate diameter depend upon the type of asphalt binder being tested. Unaged asphalt binder and RTFO residue are tested at the high temperature specification for a given performance grade (PG) binder using a specimen 0.04 inches (1 mm) thick and 1 inch (25 mm) in diameter. PAV residue is tested at lower temperatures, however these temperatures are significantly above the low temperature specification for a given PG binder. These lower temperatures make the specimen quite stiff, which results in small measured phase angles (δ). Therefore, a thicker sample (0.08 inches (2 mm)) with a smaller diameter (0.315 inches (8 mm)) is used so that a measurable phase angle (δ) can be determined. Figure 187 shows major DSR equipment.

Figure 187: Major DSR test equipment.

Figure 187: Major DSR test equipment.

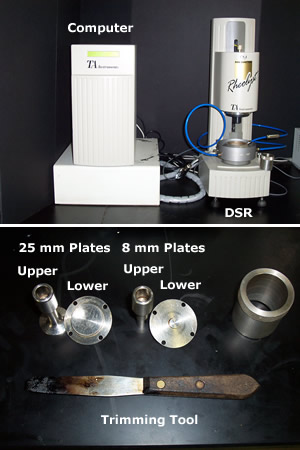

Test temperatures greater than 115°F (46°C) use a sample 0.04 inches (1 mm) thick and 1 inch (25 mm) in diameter, while test temperatures between 39°F and 104°F (4°C and 40°C) use a sample 0.08 inches (2 mm) thick and 0.315 inches (8 mm) in diameter (Figure 188). The test specimen is kept at near constant temperature by heating and cooling a surrounding environmental chamber. The top plate oscillates at 10 rad/sec (1.59 Hz) in a sinusoidal waveform while the equipment measures the maximum applied stress, the resulting maximum strain, and the time lag between them. The software then automatically calculates the complex modulus (G*) and phase angle (δ). Much of the procedure is automated by the test software.

Figure 188: DSR sample molds showing the different sizes.

Figure 188: DSR sample molds showing the different sizes.

Approximate Test Time

1 to 2 hours depending upon the number of test temperatures needed.

Basic Procedure

- 1. Heat the asphalt binder from which the test specimens are to be selected until the binder is sufficiently fluid to pour the test specimens (Video 21).

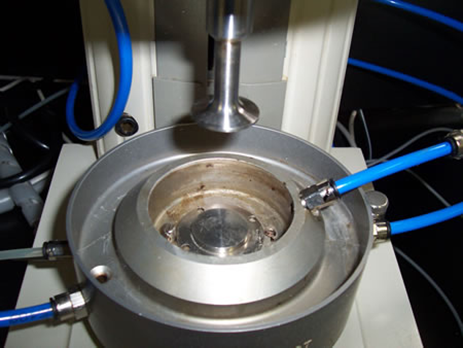

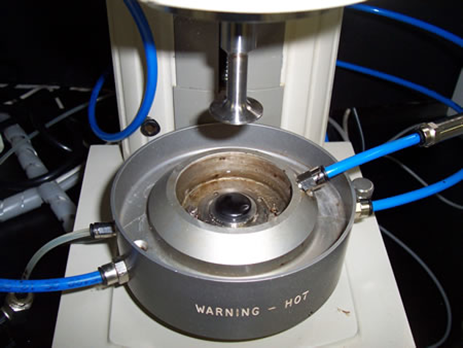

- 2. Select the testing temperature according to the asphalt binder grade or testing schedule. Heat the DSR to the test temperature. This preheats the the upper and lower plates (Figure 189 and Figure 190), which allows the specimen to adhere to them.

- 3. Place the asphalt binder sample between the test plates (Figure 191).

- 4. Move the test plates together until the gap between them equals the test gap plus 0.002 inches (0.05 mm).

- 5. Trim the specimen around the edge of the test plates using a heated trimming tool.

- 6. Move the test plates together to the desired testing gap. This creates a slight bulge in the asphalt binder specimen’s perimeter.

- 7. Bring the specimen to the test temperature. Start the test only after the specimen has been at the desired temperature for at least 10 minutes.

- 8. The DSR software determines a target torque at which to rotate the upper plate based on the material being tested (e.g., unaged binder, RTFO residue or PAV residue). This torque is chosen to ensure that measurements are within the specimen’s region of linear behavior.

- 9. The DSR conditions the specimen for 10 cycles at a frequency of 10 rad/sec (1.59 Hz).

- 10. The DSR takes test measurements over the next 10 cycles and then the software reduces the data to produce a value for complex modulus (G*) and phase angle (δ) (Figure 192).

Cold asphalt binder can develop reversible molecular associations that cause it to stiffen (called “steric hardening”). Without heating, steric hardening can result in overestimating the complex modulus by as much as 50 percent (AASHTO, 2000c[1]).

Figure 189: Upper and lower plates for the 25 mm diameter sample (left)

and the 8 mm diameter sample (right).

Figure 189: Upper and lower plates for the 25 mm diameter sample (left)

and the 8 mm diameter sample (right).

Figure 190: Upper and lower plates for the 25 mm diameter sample in

place on the DSR.

Figure 190: Upper and lower plates for the 25 mm diameter sample in

place on the DSR.

Figure 191: Asphalt binder sample placed on the lower plate.

Figure 191: Asphalt binder sample placed on the lower plate.

The calculated complex modulus (G*) is proportional to the fourth power of the asphalt binder specimen radius, therefore careful trimming will insure more reliable measurements (AASHTO, 2000c[1]).

Movement of the test plates at 10rad/sec is so small that you should not be able to easily see it. If movement is obvious, the bond between the asphalt binder sample and the test plates may have broken.

Figure 192: Sample DSR screen output.

Figure 192: Sample DSR screen output.

Testing should be done as quickly as possible to minimize the effect of steric hardening that occurs during the test. Steric hardening can cause an increase in complex modulus (G*) if the specimen is kept in the DSR for a prolonged period of time.

When testing at multiple temperatures, all testing should be completed within four hours (AASHTO, 2000c[1]).

三、 Results

Parameters Measured

- 1. Complex modulus (G*)

- 2. Phase angle (δ)

Specifications

Table 18: Performance Graded Asphalt Binder DSR specifications

| Material of concern | Value | Specification | HHMA Distress of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAV residue | G*sinδ | ≤ 5000 kPa (725 psi) | Fatigue cracking |

| RTFO residue | G*/sinδ | ≥ 2.2 kPa (0.319 psi) | Rutting |

| Unaged binder | G*/sinδ | ≥ 1.0 kPa (0.145 psi) | Rutting |

Typical Values

The complex modulus (G*) can range from about 0.07 to 0.87 psi (500 to 6000 Pa), while the phase angle (δ) can ranges from about 50 to 90°. A δ of 90° is essentially complete viscous behavior. Polymer-modified asphalt binders generally exhibit a higher G* and a lower δ. This means they are, in general, a bit stiffer and more elastic than unmodified asphalt cements.

Calculations (see Interactive equation)

DSR software performs the necessary calculations automatically. The DSR software uses the following equations:

where:

- τmax = maximum applied stress

- γmax = maximum resultant strain

- T = maximum applied torque

- r = specimen radius (either 4 or 12.5 mm)

- θ = deflection (rotation) angle (in radians)

- h = specimen height (either 1 or 2 mm)

- δ = time lag between occurrence of τmax and γmax (see Figure 5)

Then, the complex modulus (G*) and phase angle (d) are determined by:

The phase angle cannot be less than 0° or greater than 90°. The time lag can be measured in seconds and then converted to an angular measurement by dividing it by the oscillation frequency and then multiplying by 360° (or 2π radians).